Starting a Revolution: My Board Game Design Odyssey

by Philip duBarry

Revolution! is not my first game, but it's my first game to be professionally released. Not incidentally, it's also the first game I've created that other people actually enjoy playing. I'm still amazed that my game has come this far. In this article I'll describe Revolution's origins, its journey from concept to cardboard and some lessons I've learned along the way.

My inspiration for Revolution! came from reading Patrick O'Brien's The Wine-Dark Sea. Foreign agents fight behind the scenes and bribe local officials to spark revolution in Peru and Chile. My game would consist of bidding for a number of key political figures, just like the spies I read about. I drew a few rectangles and started writing down names like General, Admiral, Captain and Viceroy. I also sketched out a small city where the game's actions would take place. Then I hit a wall. I had no idea what advantage these characters might bestow.

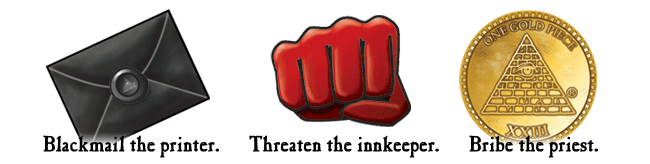

Months later, the solution finally materialized: Players would use different types of currency to win control of characters. Some could be bribed, while others could be blackmailed. Still others could be threatened with force. In the beginning I even had a fourth type of currency, called Conviction, granted only by the Priest. This turned out to be both confusing and harmful to the game balance, so it was quickly dropped. At this point the character actions seemed obvious: they would give players a combination of currency, victory points and a presence inside the city. Blind bidding also seemed to fit with both the theme and the mechanics.

Once I had spent some time working out the initial point values and character actions, I printed out a simple board and bid cards, scrounged some playing markers and started playing. This brings me to Lesson #1: Make your first prototype as quickly and simply as possible. Resist the temptation to spend hours designing detailed alien species, all with fully-illustrated cards. The more time and energy you invest in a prototype, the harder it is to make much-needed changes later. At first, I played by myself until I felt like I had something that worked. Then, I started playtesting with my family.

Lesson #2: Playtest, playtest, playtest. Most people start with family and friends because they are available and, hopefully, willing to play. This can be a blessing and a curse. Listen to their comments and praises, but always try to maintain a level of brutal honesty. The fact that your mom likes it doesn't mean your job is finished. After each game, I listened carefully and patiently to players' suggestions, and I observed the nonverbal feedback. Because my prototype was just some paper taped together, I could quickly make changes before the next game, often drawing right on the board. After about another month, the final game began to emerge.

It was at this point that I began to consider professional production. I had an interesting game that people enjoyed playing, but how would I ever be able to produce it? Lesson #3: Read everything you can about board game design and production. It turned out that I knew very little about what I was getting into. Fortunately, the Internet provided page after page of useful information. Hundreds of blogs and articles discuss all aspects of board game design. BoardGameGeek.com has a great forum section devoted to design, making it possible to interact directly with other designers. I also began to investigate suppliers and manufacturers. After reading a few success stories and many more horror stories about basements full of unwanted games, I picked up on an important theme. It's tough to make money producing a board game, but it's sure easy to lose it.

Lesson #4: Go slowly. I did not want to invest thousands of dollars in games that might never be sold. Nor did I want to spend years submitting my game to publishers. There had to be a better way. It was around this time that I found my favorite design blog, Board Games – Creation and Play written by Jackson Pope, head of Reiver Games. Jack posted almost daily about his experiences making copies of his first game, Border Reivers, and his second game, It's Alive!, by hand. He talked about gluing printed paper onto cardboard and cutting it out with a craft knife and a steel ruler. This just blew me away. The more I read, the more I wanted to make my game the Jackson Pope way.

Before embarking on my odyssey, I gleaned one final bit of advice from Jack. Lesson #5: Have a plan. He emphasized the importance of having a clear business plan before doing anything crazy. So I opened up Excel and soon figured out a way to lose $400. That's right! My first plan already had me in the hole. Starting over, I raised the price tag for my game from $25 to $30 and got rid of some big expenses, most notably setting up a booth at Origins. My revised plan had me clearing a small profit if I managed to keep my costs under control and sell most of the one hundred games I planned to manufacture by hand.

And so, I became a board game manufacturer! The first step was to acquire the raw materials. I needed a nice thick cardboard, some kind of backing material and lots of little wooden cubes and plastic chips. I bought my cardboard, actually coverstock, from Gane Brothers & Lane, a company based in Illinois. It took some email tag to settle all the details, but they proved knowledgeable and willing to help me. I purchased the bits from online retailers. Luckily, I knew someone who would do my printing on the cheap. The materials arrived, and I got to work.

I set up a simple website with a PayPal shopping cart, started a blog of my experiences, registered the game on Boardgamegeek.com and started selling my game. I ended up selling about thirty copies over about three months, several to friends and acquaintances, some to board game clubs and individuals across the country and even a few to people in Europe.

Then I discovered Lesson #6: Expect the unexpected. Unbeknownst to me, one of my games was purchased by Phil Reed of Steve Jackson Games. At the time I did not really know much about Phil or the company, nor did I clearly associate the two. So, when he asked if he could call me to discuss the game, I wasn't quite sure what to make of it. Fortunately, I gave him my number anyway, and he soon called me about publishing Revolution! We signed the contract a few weeks later.

Steve Jackson Games has done a wonderful job producing the game. Every small tweak and alteration has only made the game better. The art and materials are beautiful and add to the theme significantly. The rules are easy to understand and well-illustrated. I am extremely pleased with the final game. They have also done a wonderful job promoting the game at conventions and through their vast network of volunteers.

While I am happy with my decision to sell the rights to my game, I'm still a bit curious about how my self-publishing venture would have turned out. I think I could have stuck it out a bit longer, because, as hard as it was, I was living a dream. And I guess that's really what designing games is all about. It's very fulfilling to know that other people, many I don't even know, enjoy playing a game I made. I look forward to creating a few more games before the dream is over. A wise man once said that people only fail if they give up. If you've got a great idea for a game, I leave you with Lesson #7: Don't give up! I hope that you will pursue your dreams with intensity, and I wish you good luck in all your game design endeavors.